Notes from the Field: Donald Trump in Uganda, or: how we wanted to talk about Dominic Ongwen and ended up talking about Donald Trump

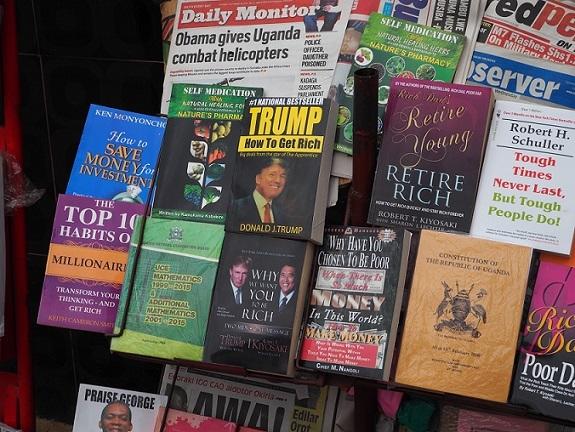

A Selection of self-help books at a vendor’s parlour in downtown Kampala. Prominently featured: the books by Donald Trump. Right next to the Ugandan constitution. (Image: Jonas Bens)

A trial is coming up before the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague. Dominic Ongwen, a former brigade commander of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), is accused of crimes against humanity and war crimes. In the early 2000s LRA fighters under his command tortured, massacred, and abducted civilian inhabitants of internally displaced person’s (IDP) camps in Northern Uganda. It was the high point of a long armed conflict beginning in the late 1980s between the Government of Uganda and the LRA rebels. When the LRA left Uganda in 2006 the long conflict had severely affected northern Uganda. At minimum 25.000 children had been abducted and recruited as child soldiers and forced wives (some estimates speak of up to 50.000), millions of northern Ugandans had been internally displaced and forced into IDP camps and thousands killed. For ten years now the violence has come to an end–at least on Ugandan territory.

The trial against Ongwen is scheduled to begin on 6 December 2016 and we have come to Uganda to investigate how Ugandans feel about the ICC and this trial in particular. From the anthropologist Michelle Rosaldo we know that emotions are “embodied thought”, those thoughts “seeped with the apprehension that ‘I am involved’” (1). We assumed that we would encounter strong emotions regarding this topic, mainly because many people are in one way or the other personally affected by the armed conflict in the north of the country. Furthermore, the ICC is highly criticized in Africa and accused of being biased against Africans and its legitimacy is severely questioned by many.

However, the most emotional moments we witnessed in the first few days of our journey to Kampala were not concerned with the indicted war criminal. When we asked people about Dominic Ongwen, even those who were particularly interested in politics, they sometimes nodded knowingly but seemed only moderately interested. More often we encountered a frown and a moment of thinking. When we helped our counterparts and explained that this was the man from the LRA standing trial in The Hague, people seemed to remember. “I believe I read an article in the newspaper about this”, said one of our friends who works for the institution where we are housed.

What we had not realized when we arrived in Kampala on September 26 was that “the debate” was about to begin. On the late morning the next day we went to Kabalagala, a quarter where many Ethiopian and Eritrean refugees live and where young Kampalans like to go out in the evening. Shopkeepers and cafe owners had put up television screens in their establishments and oriented them towards the streets. With the volume turned up, they broadcasted the televised debate between the Democratic Candidate for the Presidency of the United States of America, Hillary Clinton, and her republican counterpart, Donald Trump. People followed the debate as apprehensively as they would a football game.

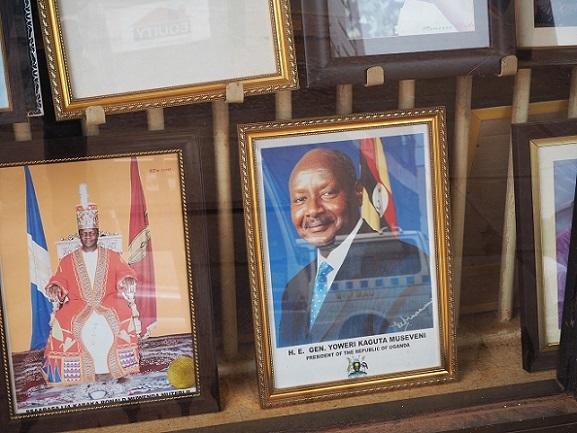

Trump, the Republican and presumably “self-made” millionaire, had hit the headlines in Uganda already during the general election earlier this year, when Yoweri Museveni was elected to his sixth term as president. The former military leader from the civil war in the 1980s, already in his seventies, is now in office for over 30 years, which makes him one of the longest serving African heads of state. Trump criticized Museveni for his unwillingness to leave office, accused him of rigging the Ugandan elections and called the Ugandans “cowards” for not staging a revolt against the government (2). These inciting comments gained him points with some of Museveni’s enemies in Uganda.

The face of Yoweri Museveni, who serves as president of Uganda since 1986, is omnipresent in Kampala. Here in the window of a copy shop in downtown Kampala. (Image: Jonas Bens)

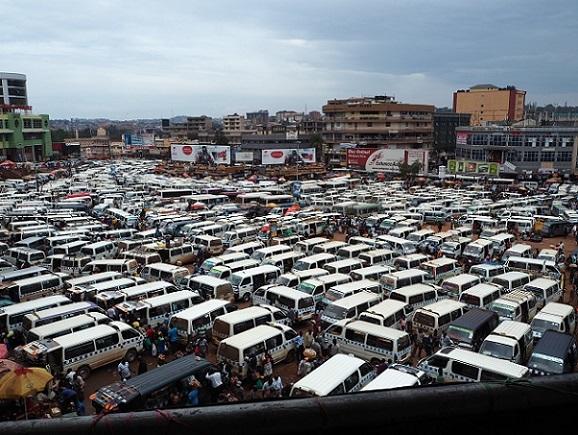

The next day we enter Owino market, the busy marketplace in downtown Kampala near the huge taxi park. While we stroll through the narrow lanes which hold every possible item–from clothes, over food, electronic articles, to office supplies–we encounter a young agitated clothing vendor holding a newspaper. He talks loudly in Luganda, the main language in Kampala besides English, and gesticulates to some of the other vendors. It is obvious he talks about politics. We hear the names Museveni and Besigye. Kizza Besigye, a former associate of Museveni’s during the civil war, is the leader of the Ugandan opposition and has lost the race for presidency against Museveni already three times.

Another young man on the opposite site of the lane begins to argue with the guy with the newspaper, similarly engaged. Somebody begins to talk about the “Muzungu” (a term used in Luganda and some other Bantu languages to describe white people). Because we think they may speak of us, we ask what it is about “the Muzungu”. But to our surprise they had not spoken about us. “The Muzungu” is Donald Trump. We are immediately included in the discussion. Often Abazungu (pl.) are indiscriminately identified as US-Americans, and the young vendor who had brought up the topic asks us what we think about the Republican presidential candidate. Urged to take a position we argue from our heart and agree that we think Trump is a “crazy guy”. The young vendor is enthusiastic. He spreads his arms and repeats our comment to the crowd in a loud voice, smiling: “These Abazungu say that Trump is a crazy guy and that we will get in trouble when he becomes president”. We hear cheering and applause. Somebody shouts “Team Hillary”, somebody else “I’m with her” (one of Hillary Clinton’s campaign slogans).

An older vendor right next to the young orator disagrees. “Being the President of the US means being the President of the whole world. This interests all of us. And Trump is a good guy.” A woman vendor intervenes: “He does not like us (maybe she means blacks or just foreigners to the US) and wants to get rid of us.” The young vendor, who had reported our comments about Trump to the crowd, opens his hands for a high five. “We’re team Hillary?” We give the high five and agree: “We’re team Hillary”. Some cheer again. When we leave the scene, the discussion goes on among them.

Owino market is close to the large taxi park in Kampala. (Image: Jonas Bens)

We go on thinking about the Trump supporter at Owino market, the one who thinks that Trump is “a good guy”. Our first idea is that Trump’s intervention against Museveni in the Ugandan election has split the country: those who support Museveni are against Trump, those who don’t like Museveni and maybe support Besigye are in favour of the Republican candidate. But things seem to be more complicated. Trump represents a type of politician who combines bragging about his personal economic achievements with a crass and social populist rhetoric. During the Republican primaries the host of the popular US television show “The Daily Show”, the South African born Trevor Noah, had broadcasted a clip in which he contends that Trump would be like an African president (3). He cuts in Trump quotations with those of African politicians like Muhamar Al-Ghadafi, Idi Amin, Jacob Zuma and Yoweri Museveni directly after. The similarities in rhetoric are staggering. But also his self-made-man personality seems to connect with many Ugandans. “Get-Rich-Easy”-books are bestsellers in Uganda. Trump has written several such books and we find them showcased at the book vendors in downtown Kampala. Donald Trump sells in Uganda.

But there is another reason that the fault lines between Trump fans and foes in Uganda cannot easily be aligned with Museveni and Besigye supporters. We have a long talk about Ugandan politics with a 19-year-old student in her last year of school. When we ask her about Trump, she laughs. “If Trump wants to get rid of Museveni, that’s a point for him”, she says smilingly. “So, you’re for Besigye, then?”, we ask. “I don’t like Besigye either”, she replies, “it should be somebody else.” We suspect that many younger people feel the same way and believe that after 30 years the elite must change and no longer consist only of the old war heroes from the 1980s. When we ask about alternatives, she names a few men we have never heard of, but maybe we will hear from some of them in the future.

After only a few days in Kampala we get on the bus north, to Gulu. In the northern part of the country many more people have been directly involved in the conflict and affected by the violence. We suspect that the interest in the Ongwen trial, and therefore the emotional involvement, will be more evident in Gulu than in Kampala. The trip takes several hours, but before we can start we have to wait at one of the bus parks in downtown Kampala until the bus is full. While we wait dozens of mobile vendors swarm the bus to sell snacks, clothing, power banks, headphones and other useful things. One of them tries to sell us books and offers us “Things Fall Apart” by Chinua Achebe. We smile and tell him we might be interested some other time. We have a look into the other books he sells. Among his selection: “How to Get Rich” by Donald Trump.

References

(1) Rosaldo, Michelle (1984). Toward and Anthropology of Self and Feeling. Culture Theory: Essays on Mind, Self, and Emotion. R. A. Shweder and R. A. LeVine. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press: 137-149.

(2) Green, Morris (2016). Donald Trump: Museveni belongs in Prison, not State House, Ugandans are cowards. Online on: politics.co.ke.

(3) Noah, Trevor (2015). Donald Trump: America's African President - YouTube. The Daily Show on Comedy Central.